A Century of Machines Laughing at Men

A Chronology of Existential Crises

Fear is the greatest mimetic force of all. It dislodges governments, replaces erstwhile stable systems of thought with unstable ones, jacks up stock prices to laughable heights (or yanks them down to unreasonable lows), and all in all, creates our zeitgeist.

It is fitting, therefore, to view the development of events in the AI world, through this lens. Some of these connections are befitting, where fear-mongering is literal. Others, where the connections serve to be symbolic, and even others, where they are wild speculation.

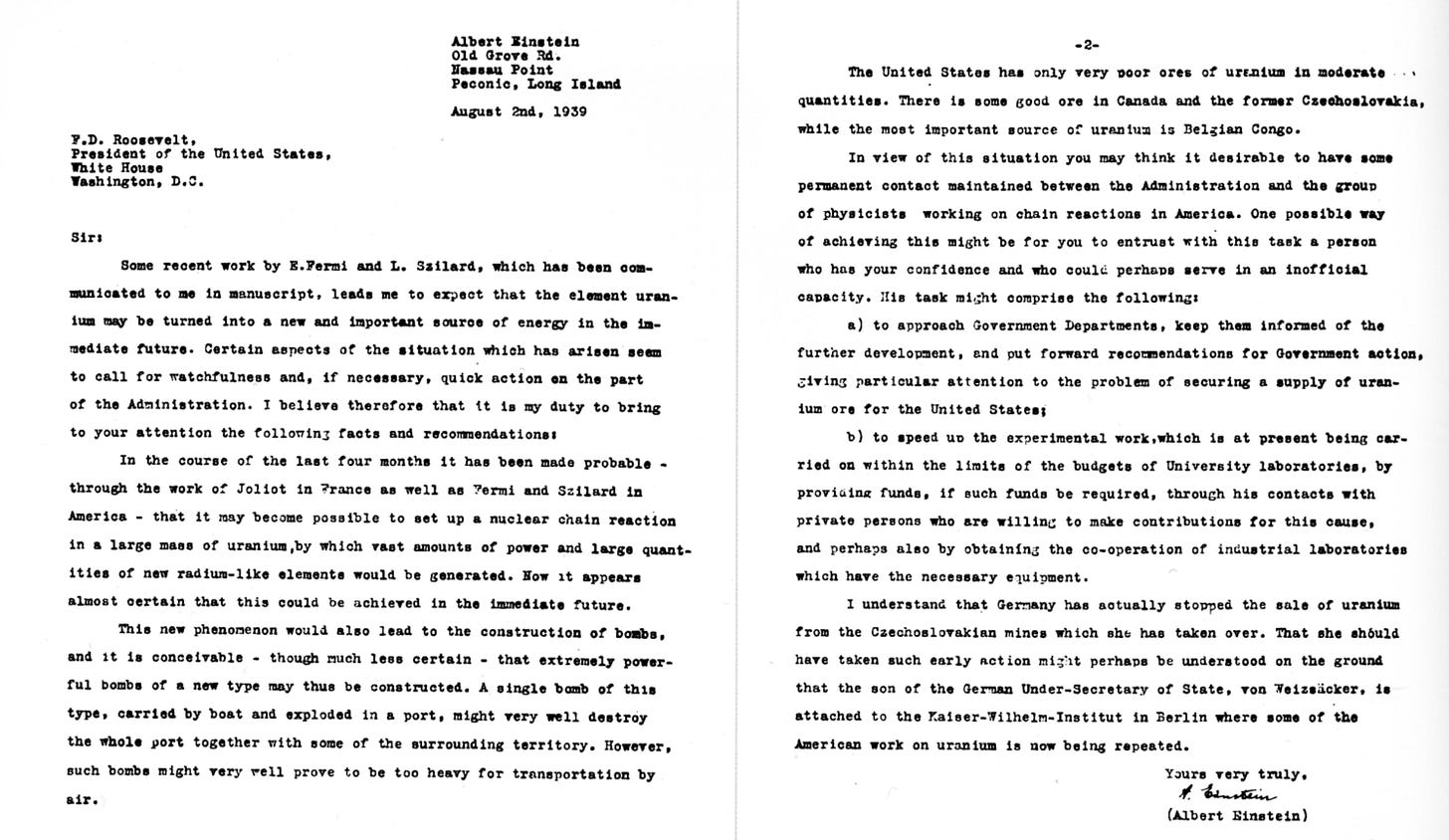

On August 2, 1939, the nuclear physicist Leo Szilard, one of the famed Martians who fled Germany soon after Hitler’s ascent to Chancellor in 1933, penned a letter to the President of the United States, Franklin Roosevelt:

What is also interesting is the signatory to this letter, long considered a pacifist in the war. Over the years, the Einstein-Szilard letter has piqued the public imagination much more than, for example, the Einstein-Szilard refrigerator. For one, Szilard had patented the nuclear chain reaction as early as 1933, so the capability of such a process was not lost on him. Second, regardless of its diplomatic language, it pointed to an existential threat: Build the bomb before the Germans do.

And build the bomb, they did. It was of course a matter of immense advantage that any German capable of building the bomb, was most likely to now be in the United States, owing to Hitler’s ideology leading to a mass clearout at the physics and math departments of Germany. David Hilbert, the grand old man of mathematics, so the legend goes, was once asked at dinner by Bernhard Rust, the Nazi Minister of Education, “How is Mathematics at Gottingen, now that it is free of the Jewish influence?” Hilbert’s response is one for the ages: “There is no Mathematics in Gottingen anymore.”

The fear that led to the clearout, led to the letter, led to the bomb, inevitably led to a greater, not lesser, existential threat ever since. More fascinatingly, this mimesis worked both ways. In 1955, Bertrand Russell drafted a letter to the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, a full decade after the Nagasaki bombing:

The prospect for the human race is sombre beyond all precedent. Mankind are faced with a clear-cut alternative: either we shall all perish, or we shall have to acquire some slight degree of common sense. A great deal of new political thinking will be necessary if utter disaster is to be averted.

Note the common signatory on the Einstein-Szilard letter and the Russel-Einstein manifesto.

Regardless of what you feel about the impact of the manifesto, considering the Cuban Missile Crisis less than a decade after the letter, and a current nuclear stockpile enough to vaporize Earth, you would at least appreciate our love for letters.

Our shared, era-agnostic love for letters is far from dwindling. Earlier this year, about 33000 people signed the AI moratorium letter, an excerpt from which has familiar echoes:

Should we risk loss of control of our civilization? Such decisions must not be delegated to unelected tech leaders. Powerful AI systems should be developed only once we are confident that their effects will be positive and their risks will be manageable.

Let’s do a simple experiment. We will modify this excerpt in two ways: Remove the word tech, and replace the term AI with Nuclear. How does it look now?

The host of think tanks and policy institutes over the decades, had a variety of chips to play with - Nuclear, Security, Strategic, etc (RIP Crypto). Now, its limited umbrella has included AI in its family. Another threat to civilization (their words, not mine), another component of existential risk. Yet, one wonders in what universe of reasoning these capabilities were deemed to have comparable degrees of significance.

Somehow, in the fog of content, the threats emanating from the BAS Armaggedon Clock at 90 seconds to midnight (the closest it has ever been in our history), are now in the same family of risk as a piece of software that by and large, is helping school and college students write their history essays?

In about a week, Meta’s Threads has proved its value proposition that ChatGPT could not in six months. In the space of twenty-four hours, Apple’s VisionPro laid a clearer groundwork for a billion dollars than ChatGPT ever could.

It is just not clear to me where the market is. But of course, I do not belong to this world. So let me frame it from the perspective of the world I do belong to.

About a week ago, Demis Hassabis of Google Deepmind confirmed the “leaked” memo circulating the internet discussing the absence of the AI Moat. Regardless of all the issues you may have had with this memo (and I certainly do), the state of cutting-edge deep learning research today, as is evident from the conference papers we have come across over the last couple of years, is a borderline fanatical overreliance on others’ model weights. Now, to the extent that the weights you are working with may or may not have come from open source, is immaterial. The orphan source is still a company. We do not have access to CLIP’s original dataset, only to its weights. It is of vital importance that you read this sentence again:

We do not have the data that CLIP was trained on.

Open Source alternatives exist, but they exist as mimics.

So the real question is the following: Does anyone think that learned weights are a good approximation of the underlying data? If you do, my next question would be - Does a stack of such approximations (weights of an intermediate model finetuned with original weights, and so on, and so forth) dilute, rather than sharpen, our understanding of the task we are working on?

There is no common base that we are building from. It is this lack of first principles, that precludes current AI research to be a significant threat to our civilization. In a sense, the stark rigour of the first principles of physics and mathematics leads to the grandeur of its oftentimes awesome, oftentimes macabre capabilities: Whether it be a complex manoeuvre on a planet hundreds of thousands of miles away on a distant surface, or engineering less than a gram of material to decimate a city.

You will hear no one asking the question: “What can Physics do?” They know fully well what it can do. But to the hordes asking the question, “What can AI do?”, my guess is that most people will not even agree on what the question means.

Taking an even bigger macro on this: Do we even care? The attention economy probably necessitates our need to move from chatGPT to GPT-4 to AppleVR to Threads to xAI in this second-order mimesis. It is probably inevitable, and at an even more abstract level, just a source of entertainment. But speak to any of your American friends whose parents were doing Duck and Cover drills when they were in school in the 60s, and that perspective certainly wasn’t entertainment. It was fundamental, physics-driven, first-order mimesis.

There is still the pesky little problem of jobs, though. That old wives’ tale of automation and job loss. I would pay for a history or social science student to work on the following Master’s or Doctoral thesis - Go back to the early days of James Watt and the Industrial Revolution, and dig up newspaper articles from that era to this. About two hundred years of op-ed columns. Analyze them, and give me the major narratives that were constructed during each era, placing them, of course, in the context of the socio-political and cultural events of the day. I think it would be a very insightful thesis. But since I neither have the money nor institutional credibility, I dived into the internet and searched for what history had in store for this article -

And a bit more perfidious, but not without humour:

Some, a bit more nuanced:

And of course, the optimists not far behind:

The full narrative three-sixty, so to speak. It was present then, it is present now, the eternal recurrence.

In fact, the economist William Jevons foreshadowed such a narrative way back in 1865, when observing the coal industry, he realized that technological progress improving the efficiency of steam engines would not, in fact, decrease coal consumption, but instead increase it, since the same progress would necessitate other sectors where more coal could be used. This observation was so powerful, that he had a whole paradox named after him: The Jevons Paradox. It is central to any such discussion about automation and jobs, as Ben Evans recently referred to in his newsletter as well.

The fallacy is in thinking that the observable efficiencies of a new technology leads to a conservation of human effort. It is so deliciously intuitive to make this mistake, but it is exactly that - a mistake. Typewriters did not replace clerks. In fact, typewriters led to more clerks. Similarly, the existence of large language models, would not lead to reduced workload for lawyers: In fact, this existence would lead them to work on far more productive tasks. The only difference between a typewriter, a washing machine, or even a snow-plougher, and chatGPT, or Github Co-Pilot, is on the issue of trust. Can we trust the solutions generated?

I have alluded to this before, on the nature of automation having closed-form solutions, as opposed to open-form solutions, and the latter is far more challenging than the former. The space of solutions for a typewriter is far more restricted, testable, and foolproof. This is not the same as asking Co-Pilot to generate a function for you. For computer scientists, imagine doing regex or a database lookup with no reliable ground truth, or a means to verify the correctness of the solution. For academics, imagine citing a paper that does not exist. For lawyers, imagine generating a fake precedent. In fact, don’t imagine it, since it’s already happened.

So, a nice rule of thumb for everyone would be to simply evaluate the closed-form nature of their jobs, or any other job, for that matter.

But it is important to remember that deeming a closed-form job to be susceptible to replacement would lead you right back to Jevons Paradox. It is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for us to claim anything whatsoever about the nature of the job. Quoting verbatim from the “Promise and Peril of Automation” by the ILO chief David Morse, almost seven decades ago:

… I would caution against exaggeration, against conjuring up a general picture of workers running around with engineering degrees and white laboratory coats. It would be a pity to blow up the technical requirements of automated jobs to the point where people get frightened about their own capacity to fit into the future.

How fitting, then, to observe that in the context of the current discussion, it is actually the blue collar workers who would be feeling the most secure! The plumbers, sanitary, firefighters of the world! Two centuries of the automation death knell, of factory floors humanless, of fully automated labour leading to a mass displacement of unskilled workers, and somehow along the way, the script flipped a one-eighty. What history is trying to tell us, if we would only listen, is that it’s extremely hard to figure out how you fit into the future.

It is no secret that deep learning struggles with common sense. This is natural, since the history of deep learning’s development had nothing to do with common sense. It had everything to do with simply recognising objects better without human intervention. Whether such recognition capabilities improved a sense of the world was not a matter of investigation for researchers then. Over the years, there have been such investigations. Flaws have been discovered and fixed. Still, extraordinary flaws have been discovered, and, owing to the zeigeist, will have extraordinary solutions.

Naturally, the next era of deep learning would be (a bit amusingly, might I add) to explore how to bake in common sense into chatGPT. By common sense, I mean at the very least, a knowledge of world concepts, and at most, self-awareness. This journey from point 0 on this scale (knowledge of world concepts) to point 10 (self-awareness), will encapsulate incredible leaps in technological progress, and as we have seen throughout this article (and history), it will be impossible for us to predict who loses out.