ChatGPT Musings

Fiddling around with OpenAI's tech provocateur, and its step sibling, Github Co-Pilot

Generative AI was the story in tech (philosophy?) for 2022, and it is perhaps useful to talk about its latest exponent, ChatGPT. Since OpenAI announced it a little over a month ago, news outlets, blogs, media personalities, tech gurus, venture capitalists, LinkedIn influencers (I am still learning about new occupations in 2022), have all been buzzing. Puzzlingly enough, I have not noticed many politicians jabbing about it. I wonder why. Are they complacent AI isn’t going to be devouring their jobs?

This is not going to be a piece on how ChatGPT works, nor will it be another boring piece on how all your jobs are going to be replaced in the future (Jobs have historically always been replaced in human history - The pyramids weren’t built with machines running digital circuits).

I have been playing around with ChatGPT for some weeks. I have incorporated Github’s Co-Pilot (an AI coding assistant) in my workflow, and this will be a piece on interesting features I have noticed in these models.

It is always useful to start at the beginning. The Generative Pre-Trained Transformer (GPT) stands on the shoulders of the Transformer, which itself stands on the shoulders of Attention, and so on and so forth. These are clever models trained by very clever people with lots of data. We are talking billions and billions of data points. Once a model does well, it then acts as a sort of cache for the next set of models (The AI world calls these models pre-trained). Essentially, you don’t lose the information you learnt in your previous iteration. That’s how you get GPT-2, GPT-3, Instruct-GPT, ChatGPT, GPT-4 this year.

But what did I try out with ChatGPT? Many of the usual things you have already probably seen online, leading users to claim “sentience”. But did we really need ChatGPT for any claims of sentience? Are we selling ourselves a bit too long?

Rewind, to 1964. Boston. MIT.

Joseph Weizenbaum designs a chat therapist that uses very simple, hardcoded rules to rephrase and reflect back to users what they just typed in. Weizenbaum intends to prove the superficiality of machine conversation, and the complexity of human expression. He calls the program: ELIZA.

What he finds instead is shocking.

The users love the program. They find it full of empathy, devoid of judgment, and truly human like in its ability to carry a conversation. Weizenbaum’s personal secretary interacts with the program for hours, eliciting a sense of comfort from it. Humans are fascinating, but also not rigorously trustworthy when labelling systems as “sentient”. The literal average Joe does not necessarily need to label chatGPT sentient. He already did that fifty years ago.

The models chatGPT leverages were trained with large datasets of text. Very large datasets of text. This is important to note, because this points to one of oldest problems in all of philosophy - Is reason a priori, or a posteriori? Is reason hardcoded in, or does reason emerge?

This is essentially why these models should fascinate us. They should not fascinate us because they effortlessly write school essays or solve simple algebraic problems. Students in standardised education systems are not very unlike chatGPT. Whether that is a bug or a feature depends mostly on how you view the world.

No, these models should not fascinate us for these apparent leaps in analytic ability.

They should fascinate us because they are a programmatic window into epistemology.

What we are essentially asking is: Do we need some degree of reason hardcoded into these models? Or do we just get more data, and wait?

OpenAI answers affirmative to the former, Google answers affirmative to the latter. It will be a Kuhn-ian moment when this conflict is resolved.

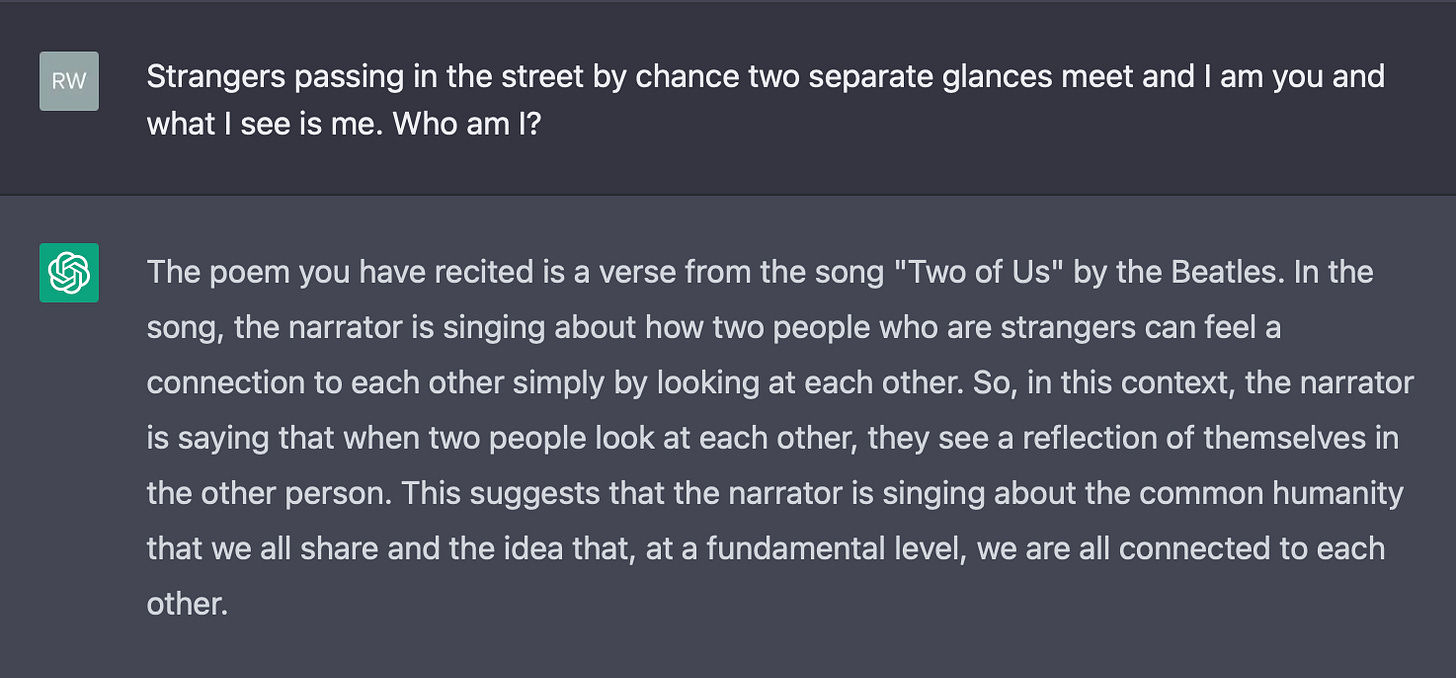

Commentary aside, let’s look at one particular example that I feel perfectly encapsulates where we are right now with chatGPT. This is a short interaction of mine with the model:

Ever since chatGPT released, the internet has melted down over its abilities and gotchas. We seem to be obsessed with asking “Hey, upstart, what can you do?”, instead of asking “Hey, upstart, how do you do what you do?”

The next five years will be unprecedented.

AND WHAT ABOUT CODING?

A bit more concrete musings subsequently - Microsoft’s GitHub Co-Pilot, an AI coding assistant. Trained with similar models. Does it really improve my workflow?

I created a simple dataframe that looks like this:

Let’s just do a simple filter operation and get a mean accuracy plot

Not bad. The text in the comments are by me, the rest is by Co-Pilot. One interesting thing to note is that Co-Pilot also suggests what you want to do from the current codebase. You can see that the two filter operations at the top are actually a single filter operation, and can be written like so:

test_df = test_df.loc[(test_df['datname'] == 'd') & (test_df['nlayer'].isin([3, 5, 7]))]

The next time you want to do multiple filters, Co-Pilot learns that you can add the ampersand sign and chain the operations together. Neat. But this is not exactly what I want. I also want the standard deviation tickers on the plot. What happens when I comment this?

Doesn’t work. This is because a more custom solution is needed. sns.catplot’s si parameter controls the standard deviation, but here it can’t do so because we already have the aggregated values in the columns, while typically seaborn would calculate the means and standard deviations from other column features. It turns out that there is a very clever hack presented here that essentially copies the same rows multiple times to estimate the standard deviation.

And finally, we loop things and plot things:

Nice. But notice how Co-Pilot couldn’t really help us here (The skeptic reader would ask at this point: Yeah, but did you instruct it properly?).

Yet.

Is it inconceivable that instead of single line comments, Co-Pilot cannot, in the future, parse through more complex instructions, like we did here? It is not inconceivable to me.

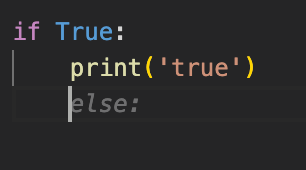

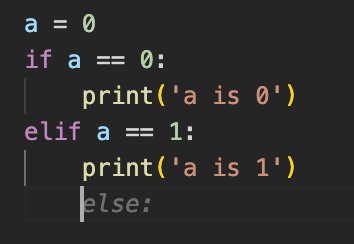

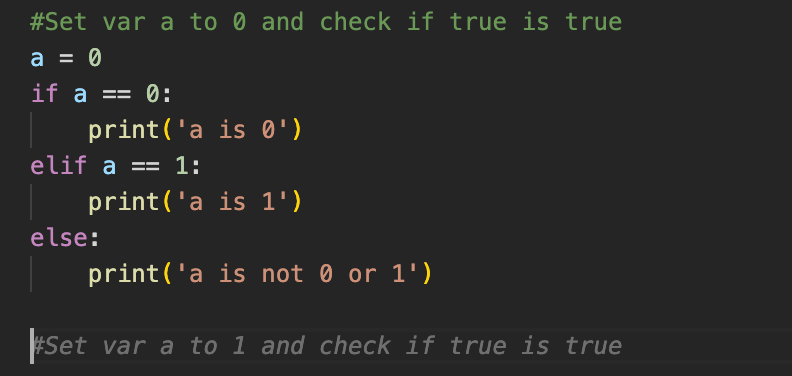

Other logical pitfalls include:

It does know the else after the if, but it does not seem to know nested logic conditions. This could be a disaster if you use its suggestions casually. It also does not seem to catch the pattern that the first else has to match the first if. In the final example, I wanted to know what it does if I provide two logically consistent but separate tasks. It repeated itself in this case.

My takeaway from using this tool (and planning to use it endlessly) is that it is incredibly useful if you know what you are doing. That seems to be good, general advice for any tool you use in the real world, to be fair. Do not use a chainsaw if you do not know what you are doing, for example.

As far as my understanding goes, the requirements for Co-Pilot at this point are:

Closed form questions

Commands that are lookup table friendly

Intense skepticism about its results

I’m in.

THE WAY FORWARD

With Microsoft testing voice commands with Co-Pilot, it seems we will get a smart coding assistant faster than a smart personal assistant, as the rules for programming are concrete, rigorous, and the input-output relationship is clearly defined. For general text, this seems a bit more challenging - Finding logical gotchas in short essays is easy and boring, finding them in a 200 page dissertation, well, could devolve into a Sokal-ian nightmare. Clearly, some problems scale worse than others.

Happy new year, and 2023 will be an absolute humdinger.

There is one big issue I see with such programs that has me worried. It is clear that these tools are powerful, and how much self-awareness we can imbue into them is a matter of curiosity. But if we have a bot that can essentially do things for us, there is less incentive to learn things on a deep level. You mention they are great "if you know what you are doing", which is a key point. When do we know what we are doing, really?

It seems that, like previous technologies, productivity boost is the first response, which is met by more expectations/needs. Regarding such purely computational needs is not too big of an issue (except perhaps for things like bitcoin), but we are already seeing how fast the tech scene, especially AI, is moving. Thus, the limits of our development are not technological in nature anymore, but biological, meaning that ChatGPT, while super useful, is powering this increase in complexity couple times over (according to these LinkedIn influences) and discouraging deep knowledge in things.

This means that we are, as individuals, incapable of keeping up with the speed of development of these areas, which threatens society not by our laziness to learn, but by our biological limits of learning things. In hypertechnological societies the underlying complexity of things is beginning to be lost on us, which means that soon enough, none of us will understand how anything works, which is a dangerous position to be in.

Specifically with respect to co-pilot (probably will discuss ChatGPT later), would like your thoughts on this cut: Co-pilot is the natural evolution in the general history of programming towards higher abstractions in manipulating chips (assembly, low level, high level languages, less obtuse high level languages, snippet-helper natural language Co-pilot, broader module level Co-pilot, complete project level Co-pilot, narration in natural language by someone with no exposure to programming, brain interface (!)...).

Re: Jobs I think the surprise is in the fact that it seems like the jobs thought to be most AI-secure are threatened to a larger degree than plumbing.